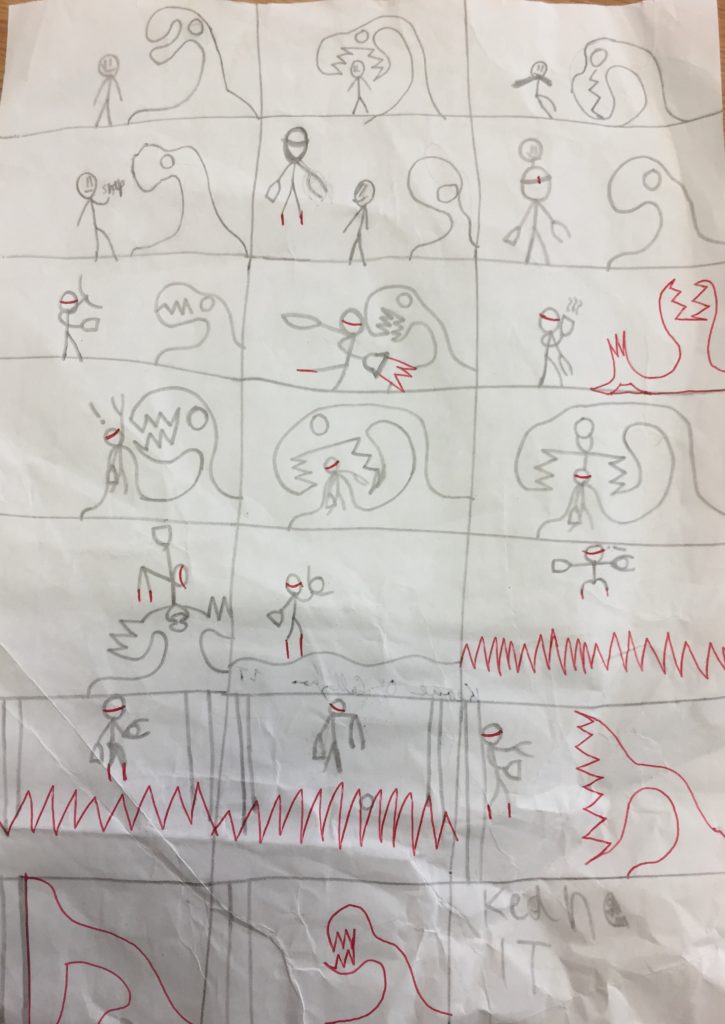

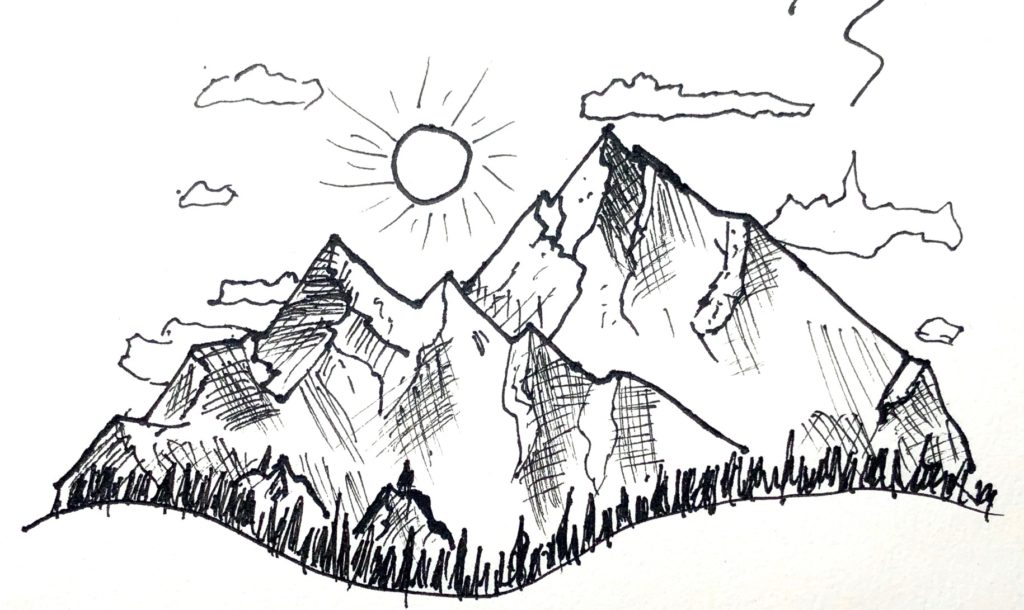

Art by Jackie Chong

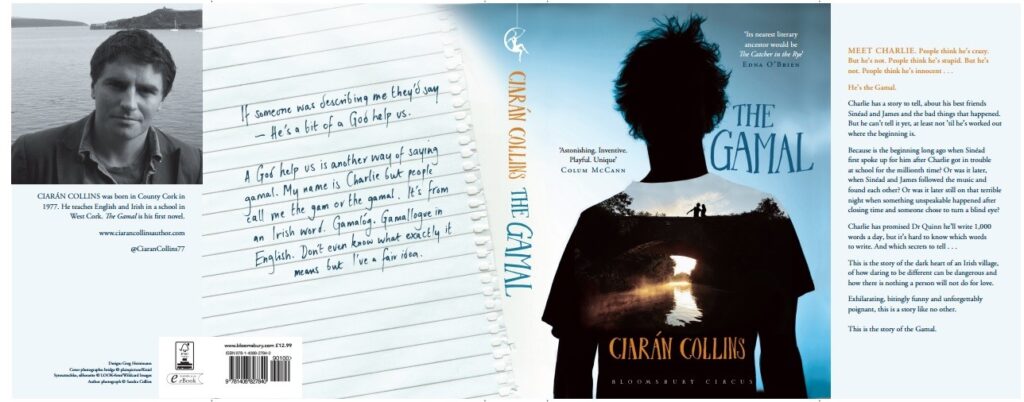

How a cover gets created…

Poetry by Alvaro García Calvo

Mientras cae el otono

Nosotros esperamos

Envueltos por las hojos dorados

El mundo no acaba en el atardecer,

Y solomente los suenos

Tienen su limite en las cosas

El tiempo nos conduce

Por su laberinto de horas en blanco

Al patio de nvestra casa

Envueltos por la niebla incesante

Seguimes esperando

La nostalgia es vivi sin recorder

De que palabra suimos inventados

(Translated to English by the poet himself)

As Autumn Falls

Shrouded in golden leaves,

We wait,

The world doesn’t end at sunset

And only dreams

Limit themselves to things

Through a labyrinth of black hours

Time leads us on

As Autumn falls

Over our house, our patio

Shrouded in relentless fog

We wait, we wait.

Nostalgia means to live without

Remembering

The word we are made of.

Ours is Everlasting

My imperfect words offend the notion.

My feelings unbound, by conscious thought.

The limit of reason, no absolute for my sentiment.

Ideas untarnished by comprehension.

Your semblance grasps my helpless senses.

My heart persuaded by graces refined.

Your eyes evoke a certain wonder,

Of the gems within their depths.

I only give breathless description.

Your presence brings an eager calm.

Your nearness invites time to escape.

Your enlightened mind enlightens mine.

With every word you say,

I hear a melody.

Our youth disapproves of such grand convictions.

Only the blurry face of finite passion.

Yet the ease of feeling you compel,

Assures me of the contrary.

That what we share is without limit.

Ours is everlasting

The Mysterious Orb

I hadn’t a clue how it had gotten there, a small box on the forest floor. It was gold and glittering, wrapped in a royal blue ribbon tied neatly into a bow on top. Taken over by curiosity, I bent down and picked up the box. It was weightless in my hand. I pulled the tail of the bow gently and the ribbon fell to the ground. I carefully removed the lid and a wisp of white light flew out and formed itself into a sphere. It slowly drifted into the forest.

Entranced by the orb I followed it down the path. It was mid-summer and the trees were dressed in vibrant green leaves, which swayed lightly in the refreshing breeze. The sun was setting but it was still warm. The forest floor beneath my feet was littered with twigs and scattered sticks. These woods were not often walked in, so it was extremely peaceful and the plants and shrubbery were overgrown. I was so overtaken by the orb that I hadn’t noticed that night had closed in.

The ball of light had started to stray from the path, floating further and further from where it had started, I followed it nonetheless. It was as if it was pulling me behind it. As I kept walking, the forest kept getting darker but the ball lit the area around me.

I trudged on through the bushes and brambles, focusing solely on the orb. The further from the path I went the thicker the undergrowth became. I trailed the orb into a large circular clearing. Then, the orb began to drift upwards. I tracked it with my eyes as it ascended into the starry sky. When I looked up I saw millions of bright orbs, drifting, tumbling and dancing around above my head, illuminating the clearing in multiple vivid colours.

I sat and watched them dance amongst the branches of the trees, backdropped by the stars. They were enchantingly beautiful and I stayed there for hours. The orbs entertained me until dawn arrived, and, as the sun rose in the new morning, the orbs dissolved into the daylight.

By Gerald O’Donovan

THE RETURN

Grey clouds were coming unfurled where the steppes transitioned into hills. Like many banners of dirty silk, they unfolded into the sky in an endless billowing. They stretched from horizon to fuzzy horizon. In their shadow the rolling, undulating steppe broke on a shore of stony knuckles, pushing up out of the earth.

A ruthless wind was rising here, and the drab apparel of a lone rider snapped and rippled. His cloak, its creases lined with dirt, rose flapping in the air, like the great wings of a monstrous bird. His attempts to flatten the rogue garment were futile and the wind was picking up on the high outcrop.

Beyond the outcrop, scrawny trees took up residence in the crannies and nooks amongst sudden boulders. The first escarpment of many descended into a valley of stone and lengthening shadows. Grunting through a face-full of fabric, the rider kicked in his heels and allowed his horse to carry him down the slope.

The wind roared, the leaves of the gaunt trees shivered, and the rider’s cloak fought valiantly to tear free. The man shifted his face in a half-grimace, the lines of his bearded face wrinkling.

The rider’s name was Tario. Not the name of one native to this Kingdom of Vorne.

Tario was here on a ‘diplomatic appointment’. Appointed over three years ago, he’d been dispatched, with encouraging platitudes from his superiors, to what had seemed an impossibly difficult situation. A Kingdom broken, an Empire at war, a Prince in rebellion and a country teetering between war and peace. This was the state of the Kingdom of Vorne, in the Year Four-Hundred and Ninety-Nine, Anno Domini.

Tario’s cloak was still snapping at his back when, peering out from behind a shoulder of limestone boulders, a tumbled-down cottage welcomed him. Despite the place’s decrepit appearance, a ruddy glow emanated from within, promising warmth.

Hopeful thoughts begun to stir in Tario. Surely they would’ve sent one of his few friends to welcome him back to Vorne. He hardly dared to hope … but perhaps Verin, the Prince, had decided to wait for him?

But mounds of broken slates were heaped beneath the eaves, the patchwork roof grotesquely reminiscent of decaying skin, shrinking off a ribcage. Hardly a place for a prince, even for the prince of country as desolate as Vorne.

Embers swam from the crooked windows, brilliant sparks of light illuminating the gnarled roots that had overrun the yard. Large, stout trees fenced the cottage’s paltry garden and constituted some form of boundary against the wilderness.

Rumbling in the sky encouraged Tario to pick up speed. He kicked in his heels and urged his weary horse to hurry past the rustling leaves.

He wasn’t quick enough. The grey clouds gave one last resounding groan before relinquishing their burden. His cloak was heavy with water and the bottom of his boots squelched as he dismounted to lead his horse through the rain and into the safety of the cottage. He made care not to trip over the roots.

The watcher waited within. Beside the watcher, hulking sleepily in the corner, was a grey horse with a dark streak running along the centre of its face. An eyelid flipped open at Tario’s entry, then slid lazily back down again when no danger was apparent.

“Punctual again,” the watcher observed, his voice dry. “I do wonder if you’ve ever been late in your life, Lord Terrace-man.”

“Malak,” Tario said tightly, thinking that he’d come all the way back only to be greeted by this dour lout.

Tario pulled his horse inside the cottage, bringing it over to an overgrown corner, as far as he could get from the doorway. After an uncomfortable examination of the dubious mould that creeped from a darkened corner, Tario pressed the bunched-up reins in a gap between two of the cottage’s old stones.

Tario turned to regard Malak, still slouching where he sat, staring into the hearth. A log burst, the chunks hissing and crackling as they hurried to escape the flames.

“Well,” Tario began, a little impatient. “What’s been happening while I’ve been gone?”

When no reply was forthcoming Tario pressed further.

“The war, Malak, how goes the war? The Prince, is he well? And has Lord Osword kept his word-”

“Yes, yes,” Malak interrupted, waving a hand to clear away some stray smoke. “Our Prince’s in the capital. Unfortunately, he couldn’t make it here to welcome you back … he’s a little busy with, well, you know, matters of state and such.”

Malak poked the logs with a stick.

“But how did your mission go, good news I hope? Will the horse-lords rally to us?”

Tario thoughts flickered to the letter that lay in his saddlebag. His only prize after a month of politicking abroad, in a land of harsh tongues and friendless faces.

“The results of my mission are for the Prince alone.”

Malak’ mouth twitched. “Of course they are.” He rubbed his knuckles, his jaw working before he uttered his next sardonic comment. “How did they refuse, politely or did they hurt your pride?”

Tario raised his chin. “It takes little to be more courteous than you, Malak.”

He dragged over a chair and joined the soldier in front of the fire. The flames pulsing, he pulled off his gloves and gingerly aligned them next to the fire.

Malak shrugged, produced an apple from a satchel he’d deposited next to the hearth and seemed to admire it for a moment. It was glowing in the firelight, so bright you’d imagine it’d burn to touch. He turned it over in his fingers before taking a crunching bite. Juice ran from the craterous wound.

Inexplicably, Tario found himself disgusted. Malak saw his expression, the chunk of apple still bulging in his mouth, and laughed.

Malak wiped his face and stood up. He gestured out to the rain.

“I apologise, Tario. I’ll extend an olive branch to you and take the first watch. Mind the horses and yourself. Soon you’ll be back to the Prince.” He took another bit of his apple, shrugged on his hood and plunged into the night.

Tario’s eyes, now accustomed to the meagre light of the hearth, lost Malak as soon as he ventured beyond the slanting doorway. The snuffling of the horses as they kneeled to rest turned his gaze back inside. Tario watched his own horse rest on her knees. Her inky eyes reflected an image of the burning hearth. Tario, his brow furrowing under the weight of expectant troubles, nodded at her. He glanced outside and caught a glimpse of Malak’ silhouette flitting across a window, already bowed against the rain.

I ought to sleep. There’s still weeks of travel ahead. He stroked his burgeoning beard. I need to shave, take a bath and food. Tario had adapted to the Vornese cuisine well, to the point that he’d begun to prefer the packed Oswordian pies over the light pastries of his home city.

Although it’s been too long since I’ve eaten the food of my own fair city. The flames exploded in the hearth and ashes were blown over his drying gloves. His distant eyes rested on them, thinking of home. It’s been too long since I went back and presented myself. Letters hardly suffice to ease the ache of a missing son. Tario bit his lip. He did not relish the prospect of returning home. Even returning to a virtual warzone fretted him less. While his mother had maintained as close a contact as she could manage, his awkward father had always been embroiled in professional matters, either absent in the halls of administration or faceted away in his study.

A thin-legged spider spun down on its web and floated between Tario and the fire. It swung there, on its slender rope, and seemed to stare at him with its multitude of tiny beady eyes. Tario frowned, and made to bat the thing away. His hand lingered in the air a second and then the fire rumbled as it consumed another log, exploding detritus onto his gloves. When Tario had blinked the ashes from his eyes the spider had disappeared.

He collected his gloves, dusted them of the ashes and put them into his saddlebag. Outside, the rain had dissipated into a misty drizzle. Malaks’ footsteps made soft squelches as he patrolled. Then they began to fade, as he moved away from the cottage.

He didn’t say how long he’d give me until I have to take over his watch, Tario noted. I’d better get what sleep I can.

Sleep did not come quickly nor easily for Tario. He lay on his side some distance from the fire, on the driest patch of earth he could find in the cottage. He stared at the flames and it seemed to him that the slim, fiery dancers were taunting him as they pirouetted and twisted in the dark.

***

Water gurgled in the roots and grass of boggy fields as the two rebels made their way north. They rode on their horses along narrow bands of dry soil that made a twisting route through patches of stagnant puddles. Ahead, another ridge of windswept hills loomed.

And then more lowlands and after those, more ridges, Tario thought wearily. He’d come this way months ago, had already seen these dull sights once, which he felt was enough. The water sucked at his horse’s hooves.

The bony legs of Tario’s horse were splattered by the time they escaped the waterlogged field. Malak’ brooding stallion had suffered similarly, breeches of brown muck now rose up the horses’ legs. Fortunately, the ground beneath the horses’ hooves was becoming firmer and the air fresher. Tario glanced back at the bog-lands they’d just traversed and saw curling mists prowling the watery trails.

He thought enviously of a proper bed and a warm meal. Vague, half-remembered fragments seemed to suggest that there’d been a village somewhere nearby.

The morning sun still hung low in the east.

Turning back he examined the view in front of him. Dull clouds blotted out any view of the sky to the north and it seemed to Tario that something malignant was lurking on that horizon, beyond those hilltops. A smell was being carried on the air, and it wasn’t his own unwashed scent.

“There’s a village near, isn’t there?” Tario asked Malak in an attempt for conversation. As they approached the apex of the hill he hoped that talk would dispel his sudden foreboding.

Malak craned his head back to look at him with one eye.

“Very good, Terrace-man. You’ve an eye for our gloomy geography.”

“It’s Lord Caryn that rules here, isn’t it? When I passed through I had to avoid Caryn’s men. Has he chosen a cause yet?”

Malak sniffed and repositioned himself in his saddle.

“Our Prince has, indeed, managed to persuade Lord Caryn to join us,” he said in a sour tone.

Tario frowned. “Caryn. They call him careful. He wouldn’t abandon the winning side.”

Malak grunted. “He’s cowardly, not careful.” He hesitated. “There’s been talk recently among the well-off folk, the scholars and the merchants that the Prince’s the winning side.”

Tario was watching Malak carefully. He urged his horse to hurry up a bit.

“What do you think?”

Malak shot Tario a questing glance. He sighed and pushed greying locks from his forehead. “The Governor here, Tenebreve, isn’t called the ‘Butcher of Voyrnestod’ for nothing. You know his reputation. He’s defeated a Vornese army in the field more than once. Now the clergy preach that our young Prince, only a boy, can defeat this monster.” He spat over the side of his horse. “I don’t believe it. Tenebreve has the men, the numbers. All he needs is for us to slip up once, then he’ll crush us.”

His voice was laden with contempt.

“The surviving lords are getting reckless now. They forget our history, the Surrender and Regrant, the Submissions, the Battle of the Novaryn. They’ve forgotten how our King was slaughtered. You know what I think, Tario? I think that the Governor, old man he is, can still hear them kicking in the stalls.”

Tario didn’t reply to that. But he was inclined to agree with Malak for the most part. Their cause had come so far in the past few years but they still needed more time. They couldn’t hope to beat Tenebreve, the Imperial Governor, right now. Not when two consecutive generations before had failed.

The country holds its breath and waits to see who’ll outlast the other. Verin needs a cool head at times like these. As Malak said, only Tenebreve would benefit from a reckless assault.

They crested the hilltop. Tario’s breath caught. Malak’s whole body shot up in his saddle and he let out a cry of dismay. His back arched as taut as a bowstring, one of his hands fumbled for his sword.

The village below had been mutilated. It was an ugly, but strangely irresistible sight. Tario found he could not look away from the devastation. The houses, workshops and taverns had been turned into gutted shells of their formers selves. The village commons had been scorched to black ash. Jumbled, blackened timbers and billowing plumes of smoke greeted them back to Vorne.

The river that coursed through the village was choked with debris. The ruins of smashed jetties leaned into water until they disappeared in the foaming torrent.

Tario’s thoughts flicked to the image of bodies bobbing, bloated and discoloured in that water. He tried to crush this involuntary premonition but he couldn’t banish the dread that was settling on his soul.

Beside him, Malak was quiet for a long moment, his body tensed. His jaw had clamped together like a bear-trap.

When he finally spoke, his voice was a whisper, barely audible beneath the cawing of the circling crows.

“Whatever you think of me, stay close, Terrace-man-” he swallowed and Tario swore he heard his voice waver. “You picked a bad time to return.” He drew his sword, steel sighing as it parted from the leather scabbard.

Arches of Northern Italy